In a Search For Identity, There is a Quest For Home

Photo by Jack Spiegel

By Jack Spiegel

All interviews conducted through a translator.

Two years ago, Doña Flavia Morales Lopez, 47, prepared to pack up what she could and begin the dangerous trek to the United States. She even went as far as contacting a coyote to smuggle her into the United States.

After she discussed it with her husband Hector, there was only one thing stopping her.

“He said to me, ‘if you leave, I can tell you right now that I’m going to die,’” Flavia said, tears welling and receding in her expressive brown eyes.

In the American political discourse, immigration is viewed through statistics.

How many migrants cross the border? How many legally? How many illegally? How many pounds of drugs have crossed the border? How many migrants are on the terrorist watch list?

It is always a question of “how many?” but a better question is, “why are they risking it all to come to America?”

It was a bluebird day at the base of Volcan Atitlan in San Martín, Guatemala, a municipality in the town of Pampojila.

Flavia Morales Lopez chuckles as she remembers meeting Hector Santos Culan for the first time. Photos by Jack Spiegel, Cameron Levasseur

Flavia and Hector grew up just a few kilometers from each other but fell in love when Hector visited her mother’s shack where she sold tostadas and drinks.

“He was very shy,” Flavia said — through her contagious laugh — of young Hector.

Don Hector Rolando Colón Perez, 48, still is very shy. He speaks in short, powerful sentences. He is a man of few words. His voice cracks – a vocal representation of his broken heart. His better half often fills the void.

When Hector was 4, he saw his father, Hector Santos Culan Sulugui, for the last time — in the streets fighting for the guerrilla.

That was the second time in Hector’s young life that his father left without a goodbye. A few months prior, Culan was brutally dragged out of his home by the Guatemalan Army. Young Hector watched in horror as his namesake was dragged away, arms tied and head masked.

Culan was eventually returned to his home, but some weeks later, young Hector watched his father depart the house in the middle of the night to get batteries, and is still yet to see his return.

That same house was eventually deemed too unsafe to live in because of the civil conflict. That was when they moved north into the town center of San Lucas Toliman.

While living in town, civilians could only safely move about between certain hours. Hector and his mother were out one night to buy food with what little money they had, when they spotted a familiar face.

Eventually, Hector and his family were able to return to their home in San Martín, one family member fewer.

Together, Hector and Flavia live on the same plot of land Hector grew up on. His old house now reduced to rubble.

For Hector, that house is so much more than just four cinder block walls.

“That house contained the memory of my father,” Hector said.

““That house contained the memory of my father.””

As Hector grew older, so did the fault line in his heart left by the disappearance of his father, and so did his relationship with Flavia.

“He would say, ‘[My] heart, [my] heart is not working. I feel like I’m dying,’” Flavia said.

Flavia took Hector to multiple physicians, each of whom said there was nothing wrong with him. His brain, his heart were physically healthy.

It wasn't until a friend suggested he see a psychologist that he was diagnosed with depression.

Hector may be a man of few words, but he is also a man of many talents. He is a father to two kids, he can cook, play the marimba and farm.

But for too long, he was defined by the disheveled Hector that was found on the side of the road. The Hector that couldn’t get out of bed in the mornings. The Hector that couldn’t work to support his family, not even his wife and kids.

Flavia Morales Lopez fights back tears as she recalls the times where she would starve herself in order to feed her children what little food they had. Photo by Jack Spiegel

“If I’m taking care of him, what do we eat? I would rather leave him at home and let God take care of him,” Flavia said, seated next to Hector. “I’m going to go struggle and fight for my children.”

That struggle and fight – while for different reasons – is why so many Guatemalans decide to make the 1,845-mile journey to the United States.

Generational Inheritance

Rural Guatemala is rife with various cooperatives: weavers, coffee growers, chocolatiers and so many more.

Esdras Cumes is a third-generation coffee farmer, and one of the founding members and general manager of the Tinamit Cooperative. He owns a plot of land about 20 minutes outside of San Lucas Toliman where lemons and limes flourish. The primary crop, though, is coffee.

Cumes speaks with a group of students about the coffee industry prior to a tour of his farm on March 10, 2024. Photo by Jack Spiegel.

Like many of the men in San Lucas, Cumes casually wields a machete attached to his belt loop. Unlike many of the men in San Lucas, Cumes’s blade was protected with a sheath.

Much to the contentment of our interpreters, Cumes spoke atop a boulder in digestible sentences. Dark blue jeans and a light gray shirt are a dangerous choice during the dry season. As soon as the work starts, that light gray turns dark gray in an instant.

Coffee is the second largest agricultural export in Guatemala, second only to sugar cane. It injects nearly $700 million into the country’s economy and lands Guatemala at No. 10 on the list of coffee exporting nations.

Before Cumes formed Tinamit, he had zero control over the prices paid for his coffee. Large, multinational companies would exploit local coffee farmers by buying beans for low prices. This left many farmers with the need to choose between making a little bit of money or making no money at all.

Cumes’s grandparents obtained the land he now owns through Guatemala’s 1952 redistribution of land law, Decree 900. Any unused land that was larger than 224 acres was redistributed to local peasants – primarily Indigenous peoples who were forced to work on farms of the rich.

“The people my grandparents worked for sent them out to work on the day the redistribution was happening,” Cumes said. “By the time they had a chance to claim their land, it was far away from town.”

Cumes is one of the lucky ones who generationally benefitted from the 18 months when Decree 900 was enforced. As the years pass, land has become increasingly more expensive, and the rich are buying back major plots of land.

“A plot of land is really inaccessible to buy because the prices are so high – 300,000, 500,000 Quetzales ($39,000 - $65,000),” Cumes said.

The average salary in Guatemala is less than $1,500 per month. In Indigenous communities, it is even lower.

That is – in part – how migration begins, Cumes said.

“If I want to try and get ahead, and I don’t have enough room on the land my family owns because we are packed together into the same little house, I emigrate,” Cumes said. “That allows me to make enough money to buy a larger plot of land.”

Cumes recognizes that while some people emigrate out of necessity, many people leave because they are materialistic.

“I feel that those people don’t believe in their country,” Cumes said. “I have a Q700 phone, but now I want a Q3,000 phone. I have a Q3,000 TV, but I want a Q5,000 TV. I have a car, but I want a bigger one. We are always craving more and more and more.”

Seventeen years ago, Esdras met his wife, Ruth, in church. He claims to have made the first move, but Ruth’s timid laugh suggests otherwise.

Ruth, too, is a third-generation coffee farmer. Her specialty: roasting.

She has had a passion for farming and producing coffee since she was young. Even when her father wouldn’t allow her to go with him into the fields because she was a woman, she would find a way.

“Once the co-op was formed, I could see that there were opportunities there and had to jump on it,” Ruth said.

Esdras and Ruth not only believe in their country, but they believe in getting ahead in their country.

“It’s my land. It’s where I was born,” Esdras said. “I’ve tried to be an example for others and say ‘We can do it here.’ I tell them it’s not easy and it’s not fast, but if every year we do things and do them right, we are going to find a way.”

Together, Esdras and Ruth share two kids — one boy and one girl.

“I also think about my children,” Ruth said. “We work hard every day, and then we go home to our children, and I think, ‘What would be the point of leaving and sending money and not being with them?’ I don’t see the logic in that.”

the land belongs to the people

Huipiles are like snowflakes – you will never find two of the same.

A huipil is the traditional, handwoven garment worn by Maya women. Your huipil tells onlookers a lot about yourself.

Each color, animal, flower that is carefully woven into the huipil signifies something unique from the range of beliefs in the Maya cosmovision to the exact community said huipil was made in.

When walking around the town of San Lucas Toliman, visitors will see mostly red and white. Red represents the sunrise, daytime, energy and power. White represents air, spirituality and notions that are not tangible.

Where huipiles differ from snowflakes is that they are strong. They’re not just physically durable, but they are a visual representation of the strong woman wearing the garment.

On the day we met with Doña Flavia, she was wearing a huipil depicting the Virgin of Guadalupe. At one point, that single garb was a quarter of her wardrobe. She was forced to sell the remainder of her clothes so that she could afford to feed her children.

Flavia’s huipil was one of hundreds seen throughout San Lucas. Many are the traditional, vertically striped red and white with icons splitting the rows, but every day, there was one exceptionally beautiful huipil that stood out amongst the rest.

Maggie Garcia’s, 33, choice for a mid-March day was a vibrant mix of blues and greens, pinks and purples, yellows and blacks and everything in between. The intricate geometric shapes, and flowers are just the background for the centerpiece.

The Maya Cosmovision suggests that alongside the physical world, exists a spiritual world.

Similar – in concept – to zodiac signs, nahuales (no-WA-lace) are a representation of one’s spiritual energy. With each of the nahuales comes a spirit animal, and a list of personality traits. Your nahual is determined by your date of birth in relation to the 260-day Maya calendar.

Garcia’s choice of huipil for March 12, 2024. Photo by Jack Spiegel

Visual representations of all 20 nahuales line the collar of Garcia’s huipil. Each housed in perfectly symmetrical squares with the same level of detail seen in a drawing.

Easily, you find yourself lost in the beauty of each thread, that is until you remember that it was all woven by hand, and the awe grows even more.

Like her huipil, there is not just one thing that describes Garcia. She is a social media expert, a leader and a seeker of the truth.

Throughout Central America, there are 28 Maya ethnic groups, each with its own traditions, food and language. Like most residents of San Lucas Tolimàn, Garcia is Maya Kaqchikel.

The Mayas have existed for well over 5,000 years. Three thousand years before Jesus Christ was born. Four thousand years before Christopher Columbus sailed to the Americas. Five thousand years before the Guatemalan civil conflict.

Up until a year-and-a-half ago, the property deed of San Lucas Toliman was missing for over 115 years, leading to exploitation and corruption from the rich.

When the deed was found, as conversation began about who the land actually belonged to in 2022. For Garcia, there wasn’t a doubt in her mind who gets the land.

“We have been here forever. The land comes to the People, and specifically the Maya people,” Garcia said.

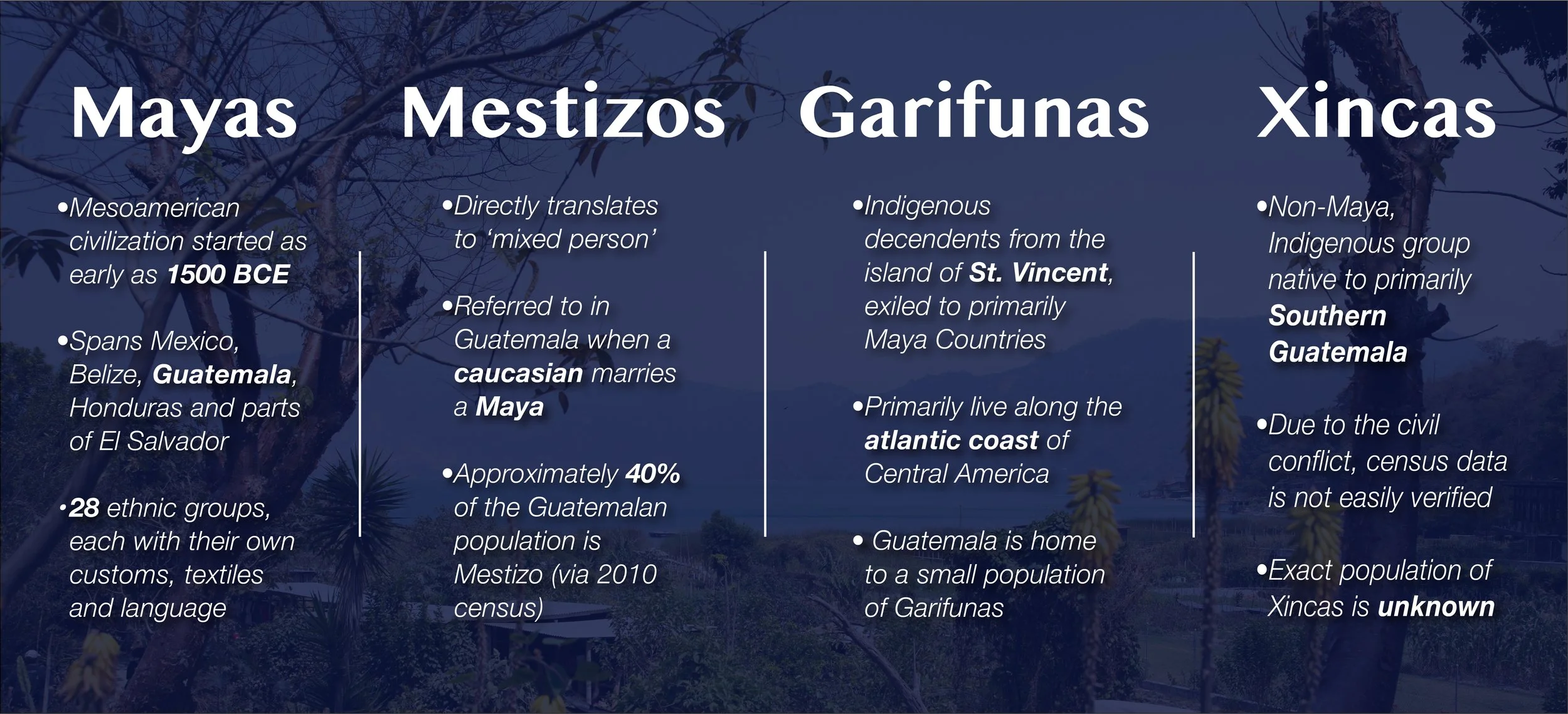

‘The People,’ Garcia says, are made up of four groups: the Mayas, Mestizos, Xincas and Garifunas.

Photo/infographic by Jack Spiegel.

One of the beautiful things about the Mayas, Garcia says, is they are generous.

“When people came, we gave them things, including land,” Garcia said. “But, among them there were bad people who took advantage of that and took even more.”

Even before the property deed was lost, the information contained within the document erroneously gave land ownership to people in the upper echelons of society.

When the deed was recovered by the Indigenous Authorities of San Lucas Tolimán, the land began to be returned to the People.

The return of the deed also reignited the process of decolonizing the mind – changing the way they have been taught to understand words and concepts.

“When we talk about poverty, one important thing to talk about is: what is poverty vs. what does it mean for a place to be impoverished,” Garcia explained. “Guatemala is definitely poor, there is a very high rate of impoverishment. But the country has resources. It is not poor in the sense that there aren’t resources available, but there is poverty.”

This, along with a consumerist society, Garcia says, is a direct link to immigration. There is a subconscious need to buy unneeded items, which is especially prevalent in poor Guatemalan communities. Not only are unneeded items being purchased, but people are going into debt in order to pay for them.

The only way to repay their debt: sell their land to the rich.

“This is why I was talking about impoverishment and the way that people create a need for things they don’t need,” Garcia said.

Another issue that is leading to immigration is the lack of education and job opportunities.

According to the Guatemala Literacy Project, up to 33% of Indigenous adults cannot read or write and only six of every ten kids make it past middle school.

There is also a psychological aspect to poor societies where people have been taught to feel as if they are unable to make things work, Garcia said.

“You become an adult and you don’t have any opportunities, so the only option for you is to leave,” Garcia said.

It hasn’t always been easy for Garcia, but she is still breathing the Guatemalan air day after day — remembering to make a few jokes along the way.

“I haven’t emigrated truly because I don’t want to leave my land, my country. I live here,” Garcia said with conviction. “One of the beautiful things about the Maya culture and Cosmovision is that as you start recovering your history, you feed yourself with that, and those kinds of things energize you.”

Maggie is a community journalist, an activist, a jokester, but most of all she is a believer in good. Each aspect of Maggie’s life is beautifully woven together like each thread of her huipil, framing her mind and heart.

reclaiming his identity

San Lucas is a mix of traditional and modern. Handmade corn tortillas being sold on the same block as the Mega Empanada from Domino’s Pizza. Smartphones tucked into the belts of women donning their hand-woven Maya huipiles. Lakeside, 12-bed Airbnb’s renting for over $300 per night, while the only roof families of half-a-dozen have in town is one sheet of corrugated steel.

This fusion of old and new is beautiful. Who wouldn’t want to spend a week in a mini mansion looking out on 50 square miles of lake in the landlocked department of Sololá, and then get authentic meals just 15 minutes inland?

Like many aspects of our lives, there is often more behind the things that give us our greatest pleasures.

Large, multinational corporations have – for years – stolen land from the Indigenous populations for the purposes of exploitation and profit. As a result, more Central Americans than ever have chosen to leave it all behind for life in the United States.

Not only are Mayas being exploited for their land, but their identities as well.

“My name is Carlos Vidal Jacinto Chico. I am 39-years-old. I am Maya Kachiquel. I became conscious of who I am when I was 28-years old,” Carlos Vidal said as he introduced himself.

Vidal is short in stature. 5 feet 2 inches, maybe 5-foot-3 depending on how tall his ponytail is. His long, black hair contrasts sharply with his pearly white teeth and his deep black eyes. Jeans and a T-shirt are what you can find him wearing most days in his restaurant, Kask’i. If he’s not at Kask’i, you can probably find him in a classroom teaching. If he’s not in a classroom, you might be able to find him grinding coffee by hand. If there is any time left in his week, Carlos can be found trying to be a contributing member of society.

But these days, excess time is a luxury for Vidal.

Carlos Vidal participates in a roundtable discussion about education at a San Lucas Tolimán high school on March 12, 2024. Photo by Jack Spiegel.

When Vidal turned 28, he began the long, and still ongoing, process of unlearning what he previously thought to be his truth.

“Once I started undertaking that process, I began to identify as a Maya Kachiquel. I began learning the Maya language. I started to think as a Maya, speak as a Maya, eat as a Maya,” Vidal said.

Through that process, Vidal realized that the Mayas are not just a relic of Chichén Itzá or Tikal, they are still alive.

“There are fakers that say things such as the Mayas went to space, or they were taken by extraterrestrials,” Vidal said. “This is all based on erroneous information which suggests then that the Maya are not here. And if the Maya are not here, then who are we?”

“If the Maya are not here, then who are we?”

Before embarking on the nearly 2,000-mile journey to the United States, migrants often turn to the Church for spiritual and physical support.

“The Church teaches people to respect the laws and the authorities of the earth,” Vidal explained. “They bless people when they're about to embark on a journey to the north. They do that knowing that what the migrants are about to do is a violation of what they just preached about following the law.”

Vidal says this antithesis is no coincidence.

What is often a migrant’s first payment after crossing the border? A donation right back to the Church

“It benefits them when people leave, and then they send money back, even though it contradicts the dogma of the Church,” Vidal said.

Contrary to western media and political narratives, violence is just one small reason people choose to emigrate.

Data from 2021 shows that of the 3.8 million people living in the U.S. from El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras and Nicaragua, 32% of them are Guatemalan. The only country on that list that has a higher violent crime rate is Honduras with 21% of the central American population in the U.S.

What Vidal says is a bigger issue is the lack of jobs and opportunities. The sentiment in Guatemala, according to Vidal, is that the way to get ahead is through a strong education.

In most Guatemalan cities, tuition is the only part of K-12 education that is paid for by the government. Supplies, transportation, breakfast and lunch are all expenses that many families will go into debt in order to cover.

Recently in San Lucas, over 2,000 students have graduated in pursuit of becoming a teacher. Only 200 of them have found jobs.

What do the other 1,800 do? Look to the North. The issue with looking to the North? The cost.

“The cost to make it to the United States can be between 30 and Q40,000,” Vidal said. “I don’t have Q40,000 – I don’t even have 10,000 or 5,000.”

Most people who emigrate are like Vidal and cannot afford the cost of migration out of pocket, so they will give a lending company their land as collateral should they be unable to pay back their loans.

“Interest is 100%, so if you do the math, they will end up paying about 250,000 Quetzales," Vidal said. “They end up spending two or three years working non-stop in the U.S. to be able to pay it back.”

And so, the revolving door continues to spin with only one place to come and go. The illusion of promise on the other side of the glass, is just that – an illusion.

Vidal’s nahual is I’x (Ee-sh), the feminine energy.

The same way a mother teaches a child, Vidal is an educator himself. Teaching and mentoring students in not only their field of study, but also the most difficult aspects of this life.

“Having identity is what has made it possible for me to look at the white man that is looking down on us and challenge him. Challenge him and say to him, I am not scared. I am no longer scared,” Vidal said.