In Guatemala, My Grief Turned Into Strength

By Olivia Barrios-Johnson

I still remember it. The way the tall trees canopied the ring of students seated below. The way the firewood in the stone pit crackled and the way the smoke rose and kissed the tree leaves above. I remember the birds calling to one another. Each with a song different from the other, and yet, synchronized in a unique melody. I remember the way the language of which he spoke was unfamiliar to me, unknown to my ear and yet felt like home. How each time he lifted the cigar to his lips and took a puff, it signified the calming inhales and exhales of my breath that I experienced in that moment.

I remember the serenity, I remember the peace, I remember the mindfulness.

I still remember it. The way the world closed in on me as if the weight of a grandaddy oak tree’s stump was slammed right on my chest. The way the fiery heat inside my body was compressed and had nowhere else to be released. When each footstep I took, felt nauseating, almost spiraling. I remember the words that my aunt spoke to me were in a language well known to my ear, and yet it did not sound like the love of my home. How each word from her mouth signified the aching and painful inhales and exhales I experienced in that moment. I remember the chaos, I remember the terror, I remember the agony.

I still remember the text I read when my world went black. The words read over the screen of my phone.

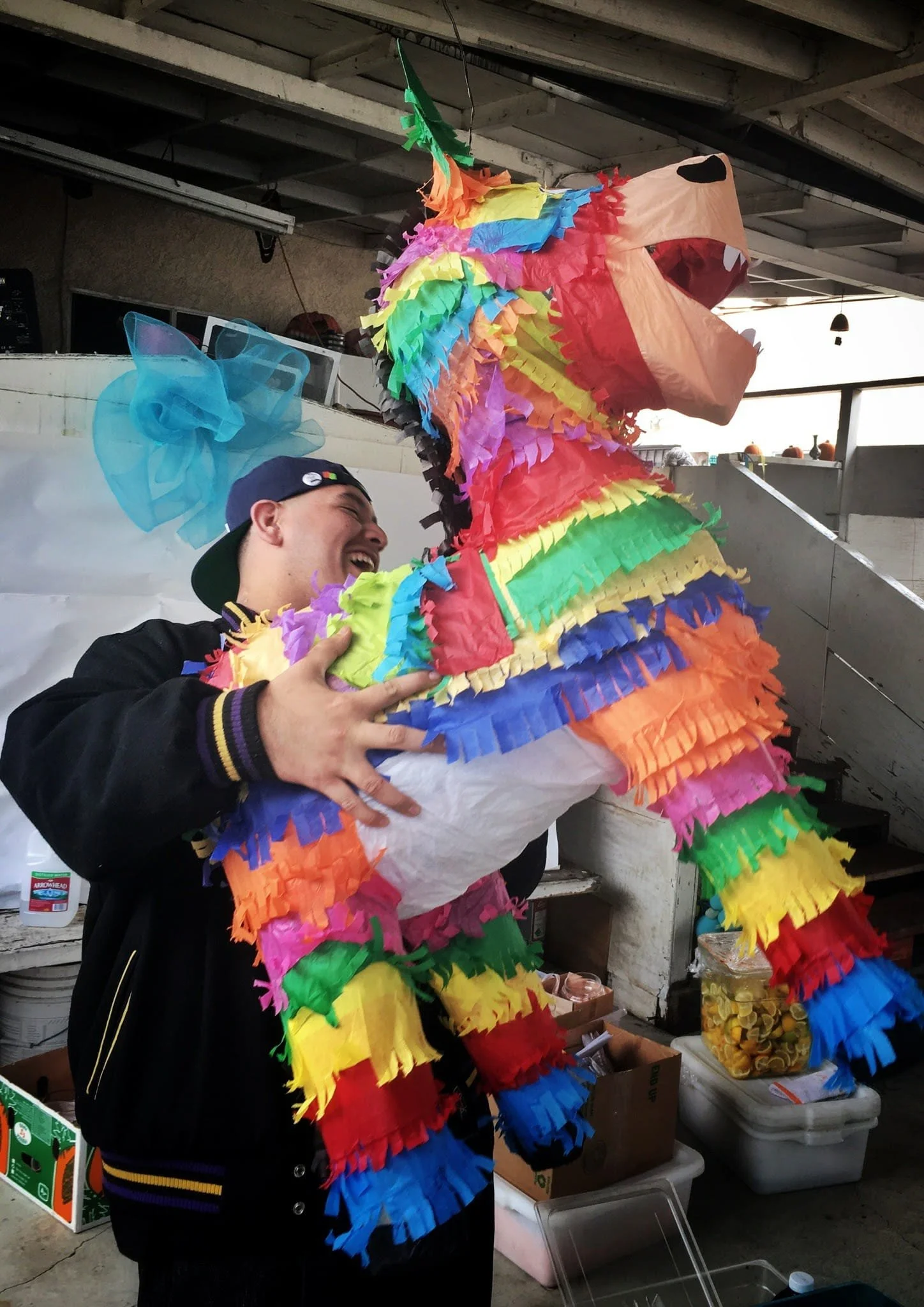

The author’s cousin Jacob “Bear” Baca during a birthday celebration in California.

Photo by Erika Morillo

“Bro he died.”

On that unforgettable day of April 19, 2022 my cousin Jacob “Bear” Baca was shot to death. He was given this nickname to honor is bear-like stature being 5-foot-9 and at least 270 pounds. As it now stands, he will forever be 23 years old, leaving behind his infectious laugh and gleaming smile. It seemed like fate that nearly two years later I’d be traveling to San Lucas Tolimán, Guatemala to experience a traditional Maya ceremony that to me, felt like home.

As a child of a Mexican mother, I grew up celebrating Día de Los Muertos, or Day of the Dead with my family. For us, honoring our family members, close friends or sometimes even friends of a friend of a friend, was normal. Decorating altars with their favorite foods, alcoholic drinks or symbols that represented who they were, helped us to keep their memory alive. It’s our way of giving our deceased loved ones a seat at the table even though physically, they are no longer here.

At the ceremony in San Lucas, spiritual leader Tata Edgar, held on to a long wooden staff and would use it to stir the fire as he “read” the flames. After a long pause, he made a proposition to the group. A group that consisted of my peers including students and faculty members from Quinnipiac University in Hamden, Connecticut. We traveled more than 3,000 miles away to hear what I felt was the essential statement that set the pace for the following experiences I would have in Guatemala.

With his staff in one hand and a cigar in the other, Tata Edgar looked once more at the fire and then at the group. Suddenly he said: “Many of you sitting here are not connected to your ancestors, and your ancestors are not happy that you’ve forgotten about them. They are not happy.”

This took me aback. It got me thinking: Have I forgotten about my ancestors? Or how Tata Edgar called them, my “antepasados.” It dawned on me that perhaps my peers had never encountered a ritual or space in which they had to be intentional and think about their deceased loved ones. Understanding this, Tata Edgar had each person in the circle say their maternal and paternal last name out loud. He explained that by doing so, it would help to put us into the mindset of honoring our family and their legacy.

With pride I announced “Barrios Johnson.” Two last names which have ironically given me the nickname OBJ. And no, I am not the 5-foot-11 American football star Odell Beckham Jr., I’m actually the 4-foot-11 journalism star. But I digress.

Tata Edgar leading the traditional Maya ceremony in San Lucas Tolimán.

Photo by Jack Spiegel

After saying my last names out loud, I thought deeply about my family history and the “lucha” or fight, within both my Mexican and Black ancestors. Mexican Indigenous people dealt with a forced exodus at the hands of American imperialism. Black people faced enslavement for over 400 years. And yet, here I was sitting around my peers, many of whom are white, and feeling like my own last name carried a different kind of burden. One that made me feel connected to the Maya communities that make up the beautiful country of Guatemala.

You see, Guatemala is also no stranger to American imperialism. Between 1960 and 1996, Guatemala experienced a civil war that left more than 200,000 people dead. About 83% of the victims were Maya, according to PBS NewsHour. It has been nearly 30 years since the war ended, however, there is still a lasting impact on the community.

On one hand, it has resulted in poor economic conditions and a mistrust between Maya communities and the government. On the other hand, the war gave birth to a “corazón revolucionario,” or a revolutionary heart. A heart that desires to continue to push forward and be a catalyst of change to improve the quality of life for the next generation. For some in Guatemala, they choose to honor their revolutionary “antepasados” as a constant reminder of the work that is left to do and to maintain the Maya practices that were established so long ago.

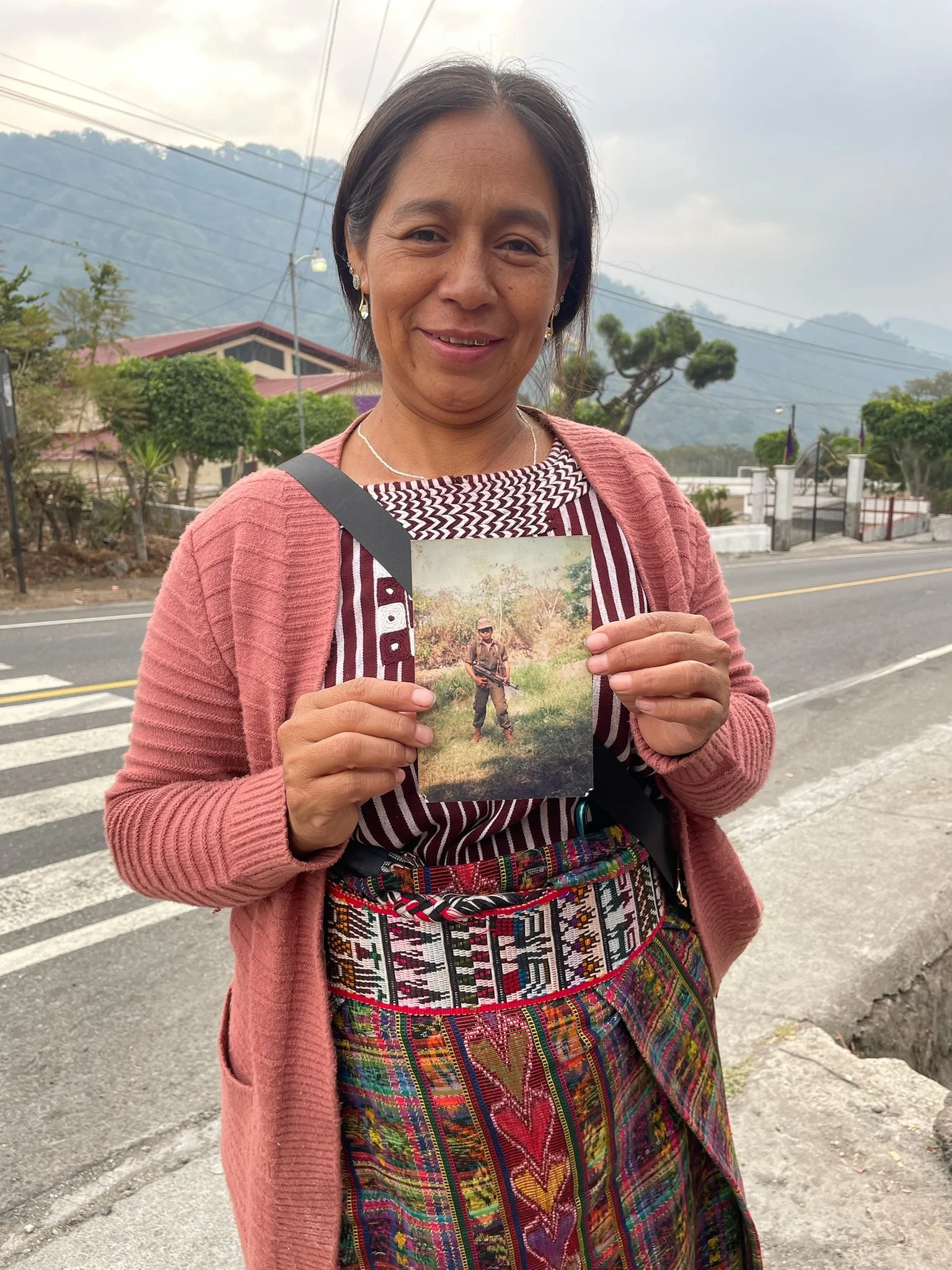

Doña Flavia holding a photo of her younger self from her time as a guerrilla fighter.

Photo by Leslie Virostek

Flavia Morales Lopez, 47, is the woman behind the “corazón revolucionario.” When she was only 17 years old she left her family of seven women to become a guerrilla fighter during the Guatemalan civil war. She wore an army green outfit with brown laced up boots to blend in with her environment which was high up in the outskirts of the mountains. She also carried around with her an AK-47 assault rifle and learned how to communicate to other guerrilla fighters via radio. Doña Flavia went hungry some days, only eating tortillas with salt sprinkled on top, undergoing extreme training that was both mentally and physically taxing. Despite all that, this was her attempt in correcting the wrongdoings that were happening in her own home country. The rebels got the peace accords with the government that they were seeking, but upon return from the mountains, she was ridiculed and ostracized by her family and community members for her involvement. She was judged for not receiving any formal education and as a result, she’s always felt inferior. Doña Flavia also still lives with the sense of longing for a better country. She was a product of her circumstances and took arms to do what she believed would make her life and that of her future generation better.

Similarly, my cousin Jacob faced his own kind of war as a young Mexican man living in the neighborhood of East Los Angeles, California. His war encompassed gang and prison life, drug abuse and the effects of systemic racism along with low socioeconomic status. In 2022, the Los Angeles County Office of Violence Prevention, recorded 510 county residents died after being shot by someone with a gun. Among those victims was my cousin. His tragic death serves as my reminder of what his life could have been like if he had the resources and means to seek other opportunities besides the lifestyle he was naturally bound to face. I feel that it is my responsibility to carry on his legacy and instead use his death as fuel to push forward in my education and professional career as a journalist.

When I asked Doña Flavia how she would like us to tell her story so that we give it justice, she replied, “I hope that [my] story will see the light through each of you. That Guatemala is still fighting. I know that you have a dream and I know that God will help you in using your heart to help humanity.”

The author looking at Tata Edgar at the Maya ceremony.

Photo by Margarita Diaz

I’d like to believe that my desire to lead with humanity is always unwavering. That my ancestors and their “lucha” did not go to waste. That although my ancestors experienced battle wounds and emotional scars, their legacy is not in vain. Doña Flavia and Jacob are and were mighty, like the mighty bears who take care of their own and shield their community, like a mother bear would shield her cub from danger.

On the last day of my trip in Guatemala, I was walking along the streets of Antigua. I remember the warmth of the sun heating up my back and the smells of the food sizzling on the grills. I took a stroll among the long stretch of tables that vendors set up to sell items like souvenirs, flowers, woven clothing and jewelry. I came across a table with a man who was selling Pandora charms and as a Pandora charm fanatic, I had to stop and check out his selection. As I scanned the tiny metal charms, I found it.

On the table lay a bear charm with “BEAR” engraved on the top right corner near the ear. It was the charm I had been so desperately looking for months; one that would commemorate my cousin. Without hesitation I picked it up and purchased it. As I rushed to slide it onto my rather full Pandora bracelet, I knew that this was confirmation that my cousin Jacob and his spirit was with me all along. He was watching over me and sent me this sign to show his love for me.

I will always remember it. The trees, the birds, the chaos and the terror. But I will especially remember Tata Edgar’s fire and Doña Flavia’s revolutionary heart. I came to Guatemala not knowing that for so long I’d pushed aside my raw feelings and emotions about my cousin’s death. In a way, this experience finally gave me the space to grieve and it ignited an ever-glowing fire inside of me. One that challenges me to put my identity as a Black and Mexican woman on the forefront as I transition to next chapter of my life. I will always remember that although Doña Flavia and Jacob never had the chance to receive a formal education or finish, I will be the one to graduate on May 12, 2024 with my Master of Science in Journalism. That my own legacy as a writer, advocate and caring human being on this earth, will be one that my future generations can be proud of. Years from now, when I too become an antepasado, I want my family to look at me as a source of resilience and love. And until that day arrives, I will always be like the BEAR and continue to pave the path for the future cubs to follow and make it up the mountain.