Photo by Jack Spiegel

Twenty-Eight Years After Peace Accords, Revolution is Still Alive in Guatemala

By Cameron Levasseur

All interviews for this story were conducted through an interpreter.

SAN LUCAS TOLIMAN, Guatemala — Flavia Morales López wasn’t sure where she was going, she just kept walking, following the lead of an older cousin whose explanation had been vague, if telling at all.

Maybe they were going to a birthday party? she thought. But they passed through the village of San Martin, past the houses of friends and family and into the dense forest that covers much of the Sololá Department.

Then the 14-year-old stepped in a clearing deep in the mountains of the Guatemalan highlands and the assault rifles made it abundantly clear where she was.

It was 1994, two years before the ratification of the peace accord that ended the country’s 36-year long armed conflict. Morales was in the heart of The Organización del Pueblo en Armas (Organization of People in Arms), the region’s guerrilla force and counterweight to the genocidal Guatemalan army backed by the United States.

Violence was all she had ever known. The war was more than twice her age. It ripped friends and family from her life. It took her husband’s father. More than 200,000 Guatemalans were killed in the conflict, nearly 85% of whom — like Morales — were Indigenous Maya.

Hundreds of miles to the east, the Unidad Revolucionaria Nacional Guatemalteca (Guatemalan National Revolutionary Unity), which the ORPA was a part of, worked to broker peace with the government.

Morales stayed in the mountains, seizing the opportunity to fight. She trained — and waited — for the moment peace talks fell through. That day never came.

The accords were signed in December 1996. The war was officially over. Morales — now 47 — still carries her demobilization card, signed by a United Nations’ representative, certifying that she gave up arms.

Flavia Morales López’s demobilization card, signed at the end of Guatemala’s civil conflict in 1997. Photo by Leslie Virostek

“The Accord for a Firm and Lasting Peace,” the agreement was titled. The last 30 years have been anything but.

Despite more than three decades of democratically-elected governments, progress has moved at a snail’s pace. Administrations controlled by the country’s elite have failed to reckon with the cost of genocide, holding onto power at the expense of the people and perpetuating the cycles of poverty and corruption that have dominated Guatemalan life into the present day.

The country boasts the largest economy in Central America, yet more than 55% of its population lives in poverty, an almost 7% jump from a decade prior. Among the indigenous population, that number reaches nearly 80%.

The country’s capacity to combat corruption — already among the worst in Latin America — has further backslid in recent years. A 2023 report from the Americas Society and Council of the Americas measured the sharpest year-to-year drop of all 15 countries on its index, only trailing Bolivia and Venezuela in overall capacity — a measurement derived from 14 different variables, including the independence of judicial institutions and the strength of investigative journalism.

Much of that decline can be attributed to ex-president Alejandro Giammattei, who held office from 2020-24. Giammattei shuttered peace organizations and violently shut down protests against his administration. In various public legal complaints, he has been accused of corruption on a number of fronts, including taking bribes in exchange for support of Russian mining operations.

María Consuelo Porras, Guatemala’s attorney general and a friend of Giammattei, led efforts to undermine the election of anti-corruption candidate Bernardo Arévalo in August 2023, causing widespread protests across the country. Both Porras and Giammattei have been publicly designated by the U.S. State Department for significant corruption, making them ineligible for entry into the U.S.

At a macro-level, these democratic shortcomings show how far Guatemala has to go, still rife with turmoil 30 years into peacetime.

At a micro-level — listening to Morales explain how she sold all but two of her huipiles to pay for her husband’s medications — they show the individual cost of the lust for power, and a lack of empathy for a population living in indigence.

“Since the peace accords were signed, I still have the same pain,” Morales said. “The people in power, they don’t care about us. Who are we? They don’t see us. We don’t matter to them, we don’t matter to them at all.”

““The reason why many of us joined [the struggle], and others long before us, is the pursuit of justice, the well-being of our people, the search for happiness and to have a decent life.””

Revolution does not end with the stroke of a pen.

Gasper Ilom understood this, even in the days when Morales first ventured into the mountains. The ORPA leader, whose real name was Rodrigo Asturias, penned a reflective message as the guerrilla group celebrated 15 years of operation in 1994.

“We have to assume that a people’s revolutionary struggle does not end with the seizure of power, in the best of cases, nor with the achievement of a satisfactory and successful negotiation,” Ilom wrote in a text preserved by the Documentation Center for Armed Moments, translated to English.

“The above opens new phases in the fight. What changes are the methods and forms, but the essence, the reason why many of us joined [the struggle], and others long before us, is the pursuit of justice, the well-being of our people, the search for happiness and to have a decent life.”

The thousands of Guatemalans who poured into the square outside of the National Palace in Guatemala City in January to protest the delay of Arevalo’s inauguration carried those same burning desires.

Their battleground? The city center. Their weapons of choice? Signs and voices. It’s a revolutionary spirit that’s evolved with the times.

La Voz del Campesino — the radio arm of the Comité Campesino Del Altiplano, a movement advocating for sustainable rural development among indigenous populations in Guatemala — had reporters on site to cover the protests.

They too play a role in this modern fight for change, existing as a souce of information and a beacon of hope for underrepresented communities.

“We broadcast the kind of information that does not appear in the major television and radio networks that are corporate here in Guatemala,” Everaldo Morales Baján, a communications assistant with the CCDA.

The radio studio of La Voz del Campesino in San Lucas Toliman. (Cameron Levasseur)

The country’s current telecommunication laws dictate that radio frequencies are awarded at public auction, making it nearly impossible for community radio stations like the CCDA to broadcast over public airwaves.

“We have some FM transformers, we bought an antenna,” Baján said. “But when we went to buy an FM frequency, they were asking for two million quetzales (roughly $257,000) to start.”

And those who do acquire frequencies are often criminalized for their work, subject to raids and prosecution for messaging that counters the narrative pushed by the government or big corporations.

So Baján and the rest of the organization's staff turned to alternative media, spreading their messages in the form of podcasts, social media and online radio.

“We speak openly about any topic. There are no restrictions,” he said. “You know no one is going to come and turn off your mic.”

Baján's tone is phlegmatic as he talks censorship. It has become an accepted reality in the country, an unfortunate occupational hazard that journalists share.

Guatemala consistently ranks in the bottom third of the world for press freedom. The Guatemalan Journalists Association recorded 171 attacks or limitations on the press in 2023, including the August murder of two journalists in Retalhuleu. Around 25 media members have gone into exile in the last decade.

“Because so few people do the work that I do, it’s very easy for them to identify those of us that are doing it and thus attack us and criminalize us,” said Maggie Garcia, a community journalist from San Lucas Toliman.

Garcia, a Kaqchikel Maya woman, writes and produces documentaries with a focus on human and environmental rights, both topics prime for retaliation. She’s seen censorship — and the effects it has — first hand.

“It affects my energy, and if my energy is off, it affects everything: my health, my mind, everything,” Garcia said.

“The thing is, here you can’t just cross your arms and stop doing what you’re doing or keep your mouth shut, that is not an option.”

There’s hope that reform is on the horizon. That the arrival of Arevalo will begin to restore balance, just as his father — Juan José Arévalo — did 70 years ago. That the unifying forces bringing together Indigenous communities will carry that momentum into the halls of congress.

But the people of Guatemala are long-familiar with the sway of money and power, polluting forces of self-proclaimed change makers.

“God has given us money, but we should be using it the right way,” Morales said. “When they’re in power, they’re always trying to get more power. Look at my family, we only have two rooms in the house, but we’re happy.

Even in the ranks of the ORPA, Morales remembers the apathy of some guerrilla leaders.

“They didn’t care if we ate, or didn’t eat,” Morales said. “Regardless of the side you belong to, power is corrupting.”

So what happens if change doesn’t come? If all options are exhausted and patience runs thin?

Garcia broaches the question. It has lingered on her mind for years, between time spent living with a guerrilla fighter in country and with Zapatistas in Mexico.

“Sitting around talking, we were saying ‘Maybe it is necessary for us to take up arms again to change the destiny of our country,’” Garcia said.

Morales doesn’t flinch at the mention. She remembers a time — just a few years ago — when the possibility was raised. Her answer is a simple one.

“Why not?”

After all, there’s still weapons buried in the mountains.

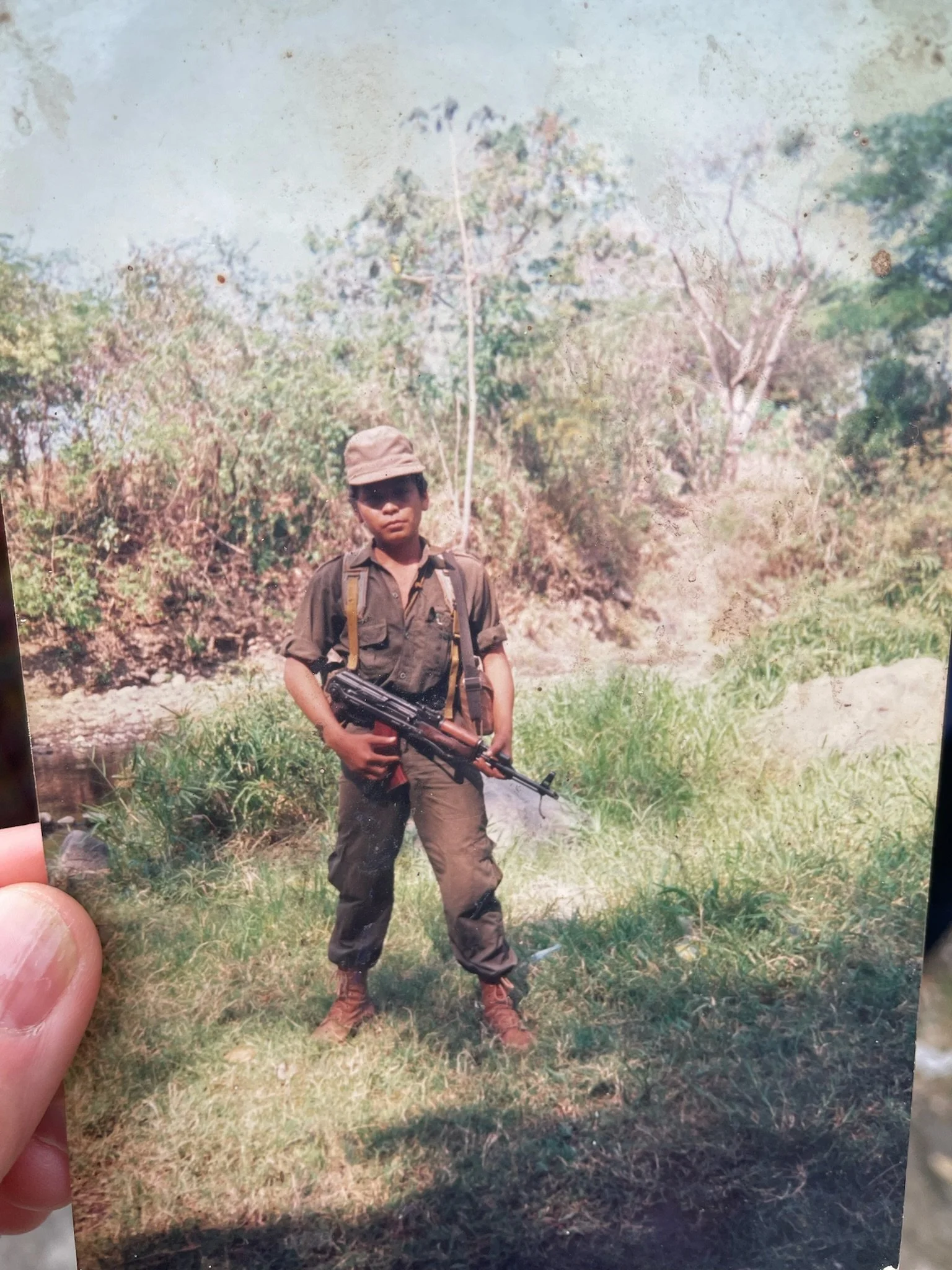

Morales during her stint with the ORPA in the 1990’s. Photo by Leslie Virostek

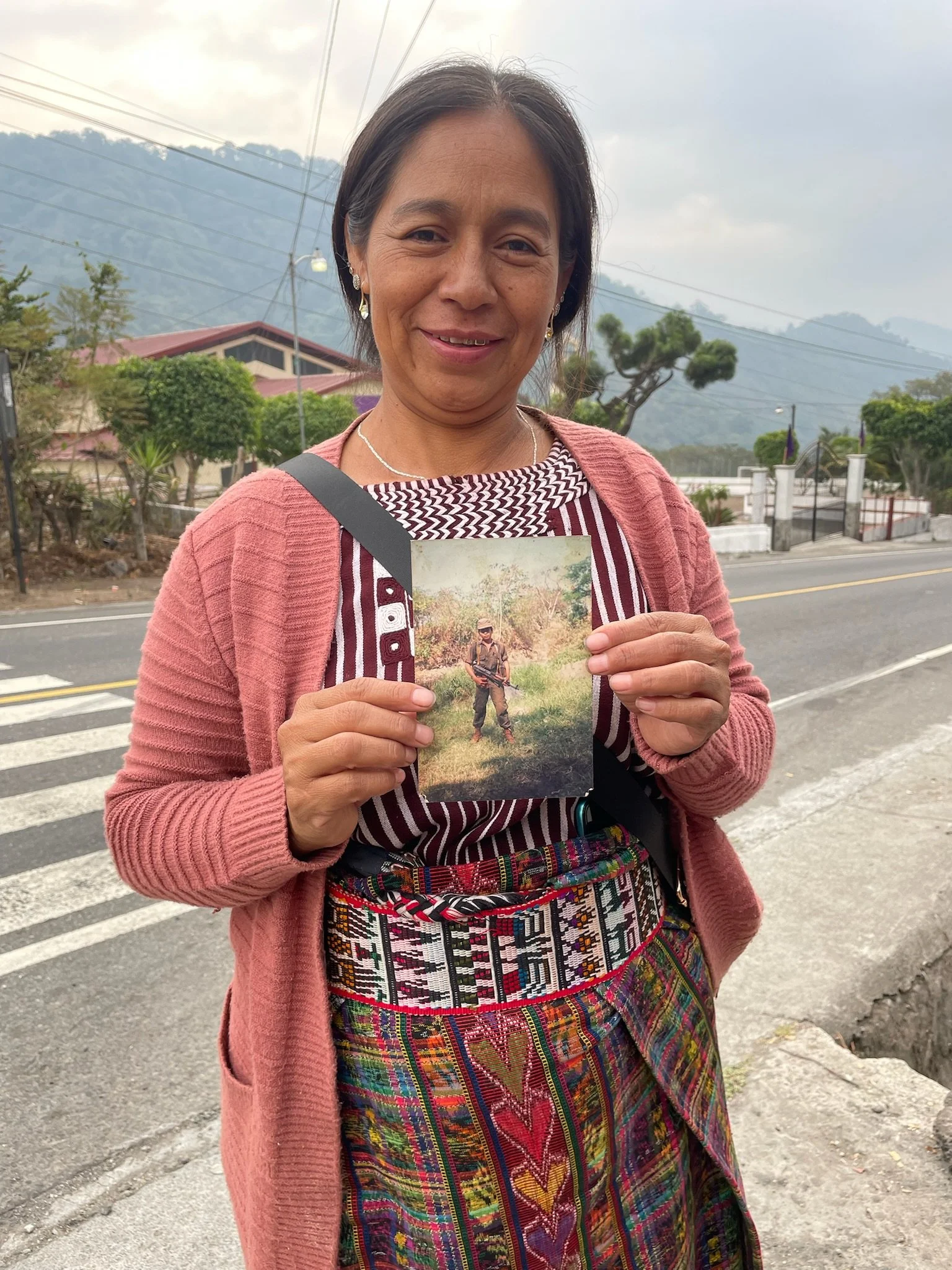

Morales holds the image of herself as a guerrilla fighter. Photo by Leslie Virostek

“I was a witness,” Morales said. “Before the monitors came, before the moment when you were supposed to surrender your weapons, they hid some of them … bombs, grenades and other things.”

Sitting beside her, Hector Rolando Colón Perez — her husband — shifts uncomfortably.

“I don’t feel it’s as necessary to take up arms again,” Colón said. “The problem is us, because we are not united. There’s no organization, there’s no heart.

“There’s a saying in Spanish, “El pueblo unido, jamás será vencido,” ‘When the people are together, they are not defeated.’ If all the indigenous people work together, and there’s many of us, we could do something. But if it's necessary, then yes, we will take up arms.”

Guatemala has never lost its revolutionary spirit, it’s merely shifted forms. But almost 30 years removed from “a lasting peace,” the country’s inequalities have become just as permanent. That reality sparks desperation, a powder keg growing in the absence of change.

“There’s a lot of people just waiting for the word, for the moment people say ‘Let’s do this,’ and they would start again,” Garcia said.

“I’ve always believed that you have to stand up for what you believe in,” Morales said. “Flavia is always ready to fight.”