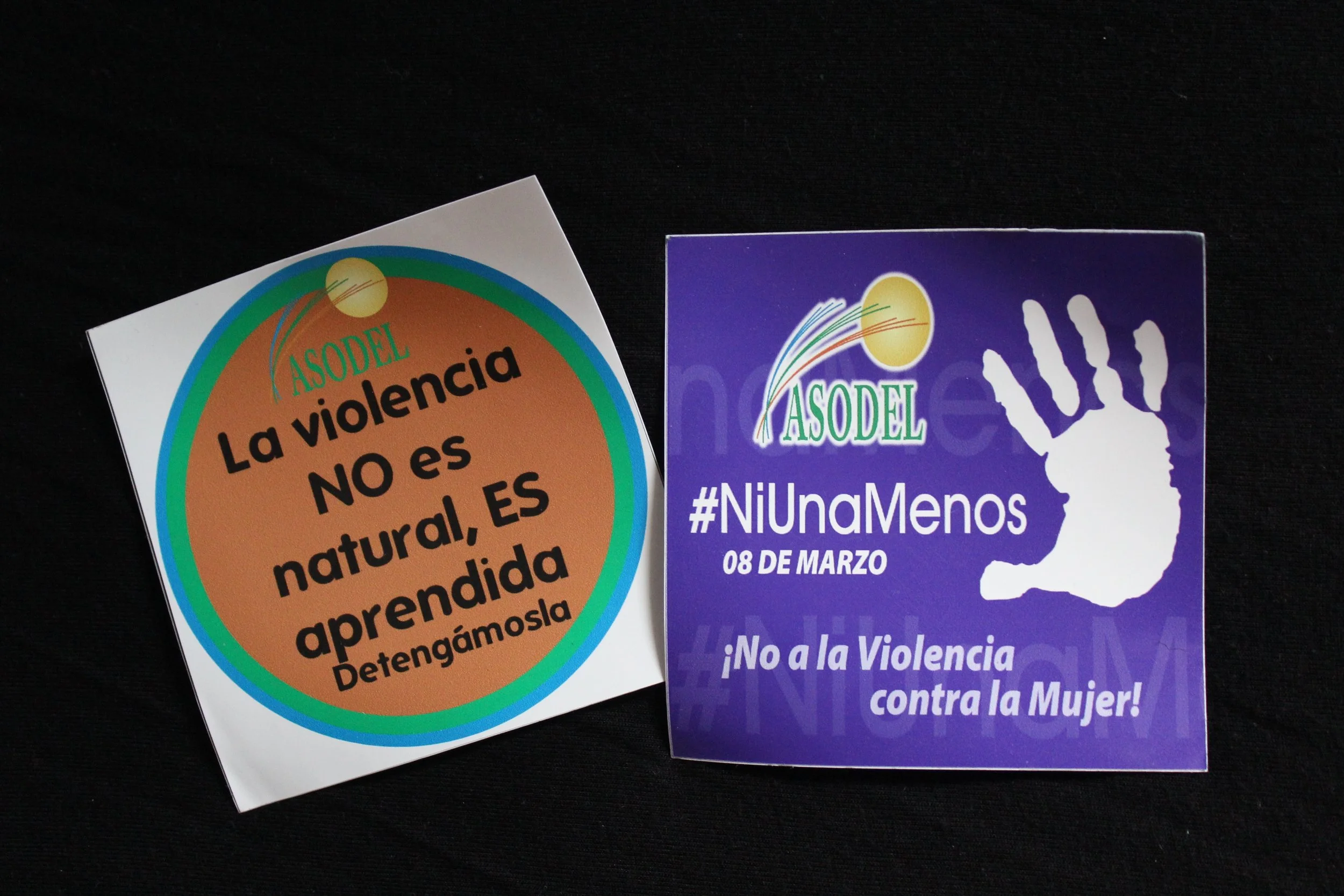

The ASODEL campaign against domestic violence uses the hashtag #NiUnaMenos (Not One Less).

Photo: Emma Robertson

Justice For All Women

by Emma Robertson

In a country where nearly everyone is against you, it may seem impossible to have a voice. But yet, women in Nicaragua are finding theirs; they are defying the numbers against them and are increasing awareness about domestic violence and sexual abuse.

The problem in Nicaragua starts in childhood. Women are taught at a young age to respect the male gender. They are taught to be homemakers, wives, mothers, and they are discouraged from being professionals. But some organizations are working to change that culture.

Esly Jarquín, a community organizer and educator at the Association for Survival and Local Development (ASODEL), an organization in Chinandega that supports victims of sexual abuse, explained that her country implants an improper mindset on most women.

“Nicaragua is very patriarchal,” she said. “Women, since they were [children], were taught that when they grow up, they are not going to study they are just going to stay at home, they don’t have the right to be outside of their house alone, and they shouldn’t talk back to men when they say something to you that is offensive or dirty.”

There is a strong sense of masculine pride in Nicaragua, resulting in a culture of machismo. This has led to a society plagued by sexual abuse and domestic violence.

According to Francisco Samayoa, a human rights prosecutor, roughly 80 percent of women have suffered some form of sexual violence. Often, both domestic violence and sexual abuse statistics are incorrect, which the 2008 Amnesty International Report on Rape and Sexual Abuse explains in more detail.

“These figures are all the more alarming given that in Nicaragua, as in other countries, rape and sexual abuse are under-reported crimes,” the report states. “Especially if they involve young girls and are carried out by members of the girl’s own family.”

In fact, violence against women has become so normalized and common that a term was created to express the homicide of a woman: femicide. It was established as a separate crime from homicide in 2013.

Samayoa clarified that femicide often originates from a man’s possessive assumptions and opinions about his partner.

“There are still people here thinking like this, ‘she is mine, or for nobody,’ and they kill her,” he said. “And if they kill her, they are committing femicide.”

As widespread as domestic violence and sexual abuse have become, there seems to be very little support from the police and the Catholic Church. Women are told by the church not to act because they are a crucial part of the family, and family is a crucial part of society. When women go to the police, they are told that issues of interfamily violence are private matters and that they should deal with the issues themselves.

“We feel more supported by the mass media than by the police.”

“So basically, where could this person go? Nowhere,” Samayoa said. “They didn’t have any place to go.”

Amarilis Acevedo Mejía, a social worker at ASODEL, agreed that there is almost no assistance from the police, and that most of the support they receive comes from a surprising source.

“We feel more supported by the mass media than by the police,” she said. “The mass media are actually our allies here in Chinandega, they work closely with us, they come with us when we’re presenting a complaint, but from the police we experience a lot of resistance.”

Even though it may seem that the situation is dismal, there have been steps made in the right direction from both women’s organizations, such as ASODEL, and from a legislative standpoint.

In June 2012, Nicaragua established Law 779, which was created to fight violence against women. Essentially, it punishes men who are committing acts of domestic violence and sexual abuse. However, it also includes misogyny, femicide, matrimonial violence, psychological violence and others.

Additionally, ASODEL has been a resource for women and children to learn more about their rights. Its main focus is education and prevention. The organization, in an attempt to rewrite the machismo culture, starts with the children. It teaches youth in schools to object to and denounce domestic violence and sexual abuse. ASODEL also organizes workshops for teachers in which they learn how to identify the warning signs of domestic violence and sexual abuse in their students.

Acevedo confirmed that the educational aspect of this issue is crucial in improving the lives of women.

“Teaching them about sexual and reproductive rights empowers young women to realize that they are not defined by what society tells them, that they have other options, there are other things they can do in life,” she said.

From these programs that have been implemented in schools for both students and teachers, ASODEL has seen positive results. These results have extended beyond the schools as well, and have improved general opinions about how women should be treated.

“Some of the changes we’ve achieved [include] … more support in the communities when there is violence,” Acevedo said. “We know there are more things to work [on] and many things to change with physical violence, but we’ve seen that when somebody kills a woman it’s not just another woman.”

Not only does ASODEL help spread awareness in communities and schools, but it also benefits women themselves. Jarquín has a new understanding of what she deserves.

“Now that I’m a part of this organization, I know my rights, I know that I don’t have to stay silent about the injustice,” she said. “[This is] not just for me, this is for all women.”