Reclaiming the Sea

A fishing cooperative on the Pacific fought back and won big

By Rachael Durand

In the small town of Tárcoles, Costa Rica, starting 30 years ago, one organization created waves in governmental policy to sustain its livelihood of artisanal fishing.

Tárcoles is a community of about 5,000 inhabitants alongside a strikingly blue coastline on the Pacific. About 80 percent of residents take part in small-scale fishing as their main source of food and income.

Jeannette Naranjo

Naranjo is the only female captain in the fishing cooperative. Here she shows a group of visitors appropriate fishing netting.

Photo by: Rachael Durand

Jeannette Naranjo is a 45-year-old artisanal fisherwoman from Tárcoles who began fishing at a young age. Her story of finding purpose in the ocean closely matches the story of her community, which had to fight corporate interests to continue fishing while preserving the area’s aquatic population. Fishing was always what she wanted to do, she said.

“It was part of my family,” Naranjo said. “I always saw my father fishing when I was little and I always liked it.”

The community is not only a fishing community. Multiple generations of families have called Tárcoles home for decades.

“In fact, we all know each other,” Naranjo said. “Not only that, but this town is so small that a lot of us are related, we’re a very large family.”

Like many large families, the people of Tárcoles came together when faced with a common problem.

The problems briefly started in the 1950s and ‘60s when Spanish fishermen came to the Costa Rican shore, emptied the oceans of wildlife then sold their boats to the Costa Ricans.

The severe loss of fish along the coast of Tárcoles led to the Tárcoles Fishing Cooperative (Coope Tárcoles RL), which was established in 1986 by a group of local fisherpeople who came together to support each other via resources and funding.

Despite its efforts, the local fisherpeople could not sustain their small scale artisanal fishing because international commercial fishing companies had taken control of Tárcoles’ waters. The activities of the commercial fishermen, who sent many ships to troll the coastline, succeeded in destroying any remaining fish.

By the 1990s and 2000s, entire species of fish were gone from the area. The lack of fish meant no food and no income for the families of Tárcoles, including Naranjo’s.

“Being a fisherperson is challenging because not all the times are good times,” Naranjo said.

To revive not only the fish but their livelihood, Coope Tárcoles RL brought together local artisanal fisherpeople to create change in governmental policy through community discussions, research and advocacy.

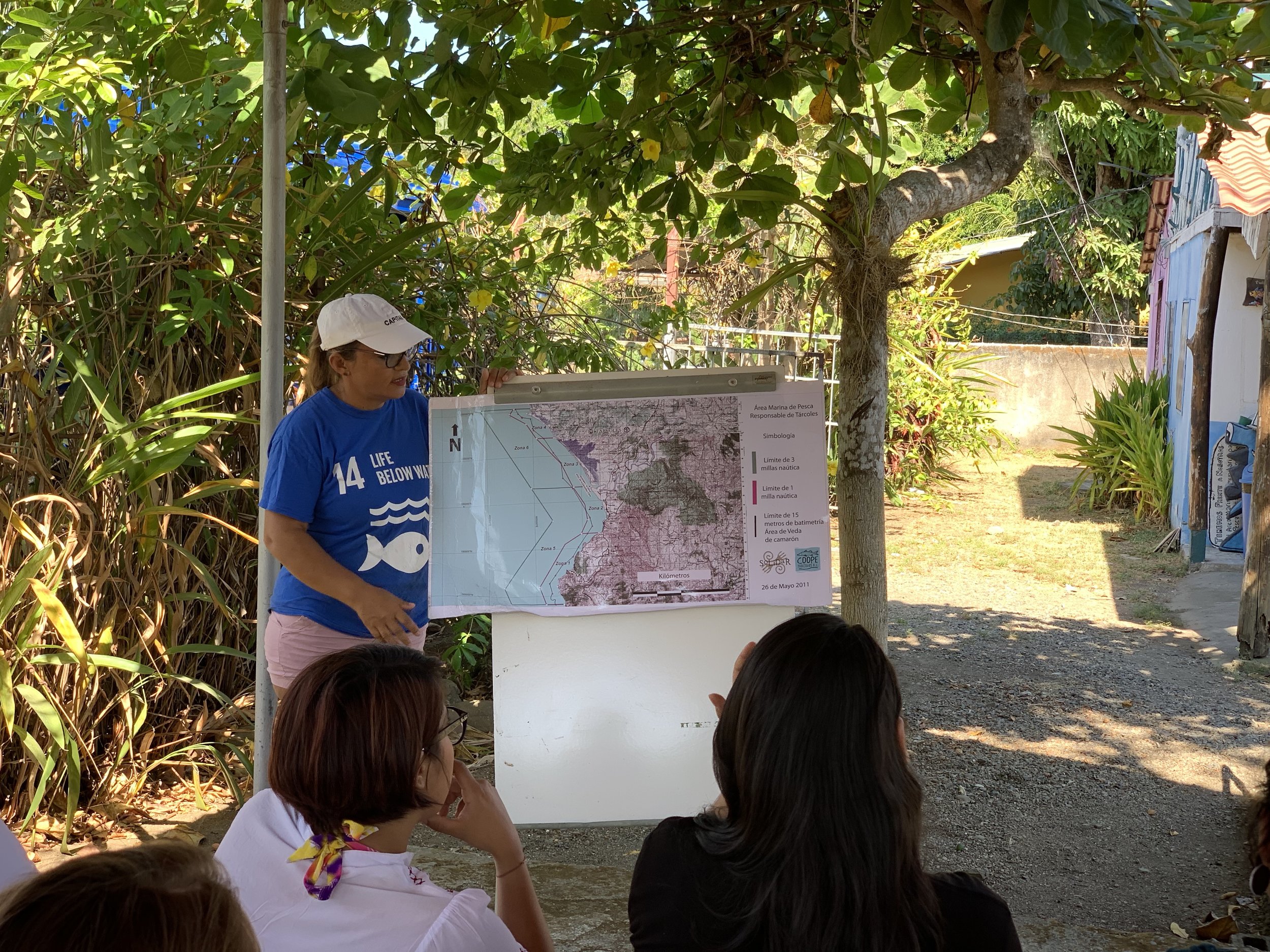

In 2005, Coope Tárcoles RL developed a database that recorded the area’s daily catches as well as the methods used and the corresponding locations. After compiling the data, Coope Tárcoles RL used the information to educate and inform the government agency responsible for marine affairs on the problems plaguing the Tárcoles fishing village and the surrounding sea in the Gulf of Nicoya, according to a report produced by the Equator Initiative.

As a result, zoning was implemented to protect areas of environmental vulnerability and to identify areas of conflict. Naranjo, the fisherwoman, explained that thanks to these measures, the coastal wildlife returned and the community was able to begin fishing commercially again.

Outline of the zoning area proposed by Coope Tárcoles RL to local government officials based on the data they collected.

But the cooperative didn’t stop there. As the Equator Initiative report points out, one of the most important innovations that came out of this process was the Code of Responsible Fisheries, the first of its kind in the country. The document gives fisherpeople a blueprint for responsible fishing through best practices in the trade.

Despite their successes, the Tárcoles community is still combating international commercial fishing companies in order to continue artisanal fishing. For instance, Naranjo explained that the cooperative relies on a large company to distribute its product.

“We are trying to do things here the right way,” Naranjo said. “This company that we work with doesn’t really value what we are trying to do, so they don’t weigh that against the prices that they are assigning to the fish.”

The community sells a small portion of its catches to international retailers to make extra money, but those companies do not take into account the time, effort and style of fishing that the people of Tárcoles practice, she explained.

“When we catch something and we know how much the price should be, we’re excited because we have a good catch,” Naranjo said. “Then we come back and discover that they lowered the prices.”

Artisanal fishing is a hands-on process where only a few men, or women, aboard a small-scale boat use line and hooks to individually catch fish whereas commercial fishers simply throw giant nets into the water to catch anything to make a profit.

“They are only interested in money regardless of where the fish are coming from.”

The fish are coming from people like Naranjo who are not only changing the conversations surrounding artisanal fishing but who actually love what they do.

As a native of Tárcoles who grew up watching her father fish to now being the only female captain in the cooperative, fishing is all she has ever known.

“If you get involved in this industry it’s because you love it,” Naranjo said. “Because you have it in your blood.”

Being only one of eight females in the fishing cooperative, Naranjo said she wishes more women would see the beauty in fishing.

“I think it would be very interesting to see other women experiencing this,” Naranjo said. “What it is to pull the netting up, what it is to see the big fish that you pull out. It’s quite beautiful.”

The beauty in fishing is its ability to bring together communities, families and fisherpeople to create a culture that promotes support and success.

In Tárcoles, fishing is their life, their income, and their job. Fishing is their culture.

“Especially on the coast, because it’s our main source of income, it gives us a trade, something to do,” Naranjo said. “For those of us who don’t have an important resume that would get us entry into another business, we can always do this. The sea doesn’t ask for your resume.”