For Nicaragua's Poor, a Future in Doubt

Text and photos by lindsay pytel

Children are dreamers by nature, thinking the sky is never the limit. In Nicaragua, even when the dreams are more practical, there’s still a question of how likely it is that those dreams will become a reality.

In a women’s center in Chinandega, Nicaragua, the Asociación de Mujeres Luisa Amanda Espinoza, four English-language students talked about how they aspired to be a surgeon, a pilot, an engineer and a doctor. In Chinandega, a city about an hour outside of León, the air is stifling hot. So hot, one sweats indoors without exerting energy. The children’s teacher, Karen García, explained that the young students received a break in their tuition payments so they could afford a three-month course to learn English.

García listened as they spoke of their aspirations. It will be difficult for those dreams to become reality, she says, and, most likely, won’t.

“Most of the careers they want, they don’t offer those kinds of careers at public universities, only in private,” Garcia said. “It’s really expensive in [Nicaragua] for parents like theirs… because they have jobs like cleaning houses or, you know, that type of job that doesn’t make that kind of money, so it’s going to be really hard for [the children].”

Karen García

In Nicaragua 11 percent of children ages 15-24 have absolutely no formal education and over half [58 percent] have not completed primary or secondary schooling, according to a 2014 study by the Education Policy and Data Center. According to the same research, in 2014 there were 934,000 children enrolled in primary school, 320,000 enrolled in lower secondary school and 146,000 enrolled in upper secondary school.

“In Nicaragua, the academic year begins in January and ends in December, and the official primary school entrance age is 6,” according to the Education Policy and Data Center. “The system is structured so that the primary school cycle lasts [six] years, lower secondary lasts [three] years, and upper secondary lasts [two] years.”

In 2014 more than 6 million people made up the population of Nicaragua and since then the number has continued to increase, according to Worldbank.

Combining the research of both of these sources, only 1,389,000 children [or 23 percent] were enrolled in school in a population of more than 6 million people.

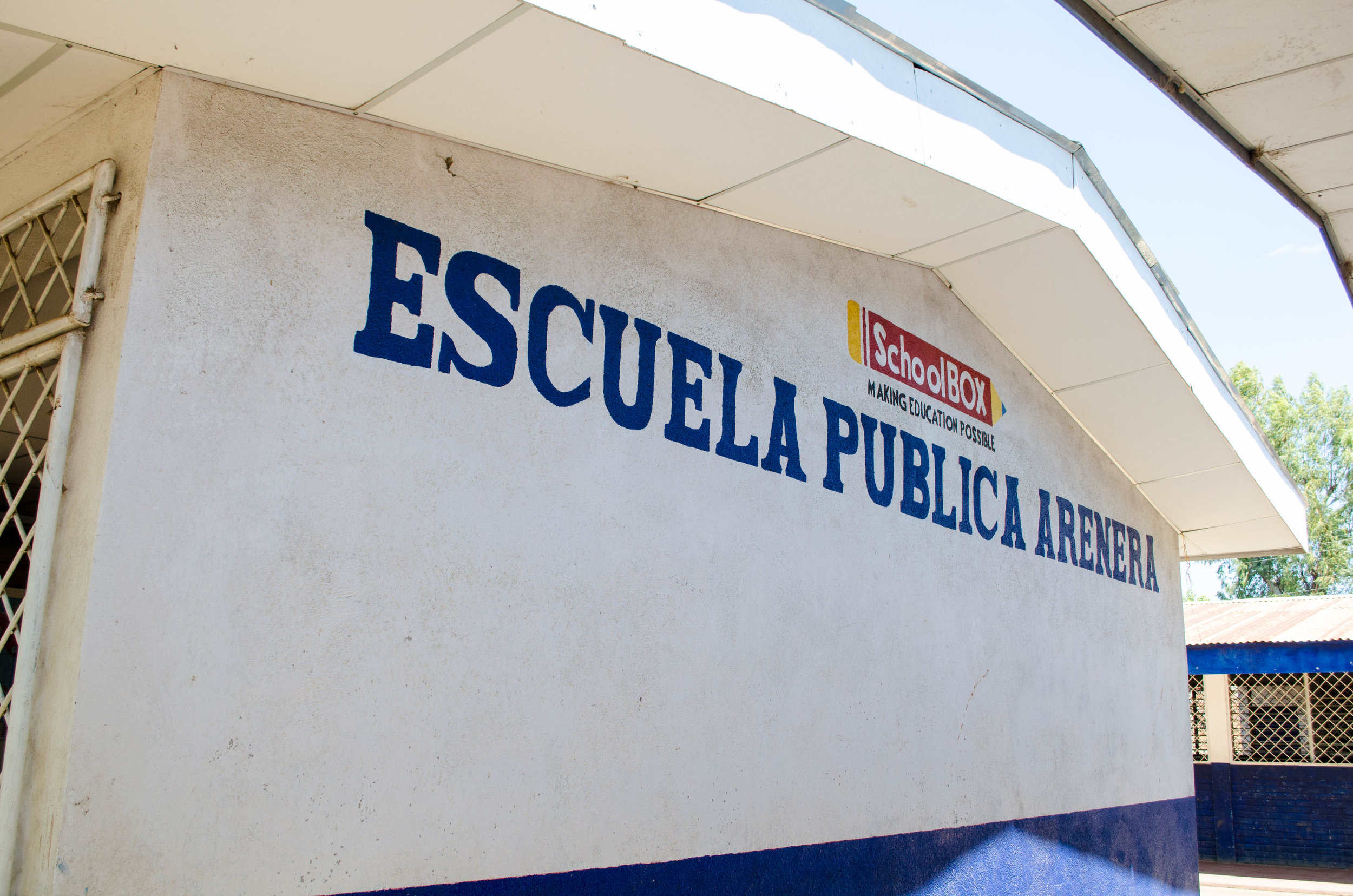

In the rural community of La Ceiba, 15 minutes from León, dust is everywhere and children pour out of the classrooms excited to go home for the day. Teachers talk about the complex challenges students face daily in regards to their education.

An elementary school teacher, Marta Pichardo, says that students in rural areas face a series of challenges, including poverty, lack of transportation and family obligations.

“One of the reasons they have difficulty becoming professionals is because they don’t come to school on a regular basis, they switch to the Saturday program,” Pichardo said. “That way they can help working in the fields. It’s very difficult for them to become professionals, even if they want to. They just don’t have the support.”

Marta Pichardo

In her class, sometimes students are required to pay for photocopies or materials for their homework. Recently Pichardo assigned homework to her students to create informative posters explaining different areas of human anatomy. Pichardo says out of 36 students, only four did the assignment.

“Parents don’t make the sacrifice so their child will get beyond primary school,” Pichardo said. “For example, sometimes we see and put ourselves in the position of the parent, so we give them some homework and if they have to spend 3 cordobas to do their homework, they don't do it. When we see that that happens, we try to be flexible because we can’t make those demands of them.”

The exchange rate [GDP] is 29.81 cordobas to $1, according to Google Finance. In other words, 3-4 cordobas is about 11 cents.

Homework

Nearly 30 percent of the population in Nicaragua lives below the poverty line, and their per capita income as of 2016 was $5,300, according to the CIA World Fact Book.

Pichardo mentions public school is free, which is why most children attend primary and secondary schooling. However, once they’ve completed the lower forms of education, it gets more difficult because university is more expensive. She says she feels children have the opportunity to achieve their dreams… but only if they receive a scholarship.

Though university may be unlikely for most, these teachers hope their students will receive as much education as they can.

“I think if we have more education, the country will be safer,” García said.

García says she can’t complain of all the outside help other countries, like the United States, have provided for her country. But as she recounts some of the things she has seen, the issue of poverty rears its ugly head.

“The problem is here,” García said. “The problem is when [Americans] send money or something for the little kids and the [funds] don’t go to them.”

García explains that she has seen instances where books have been sent from the United States and people sell them on the streets, instead of going to the children they were intended for. She suggests that some Nicaraguans don’t see the damage that failing to provide a decent education for their children will do to the country.

“I think the problem is us, Nicaraguans,” she said. “I don’t know why we always try to take advantage of something that we shouldn’t. [We need to] change our way of thinking, we have to know that when we take away things from kids, we take away things for our future, too, as a country.”