“We think differently than the others”

Maya educatorS look to establish a new way to preserve Their ANCESTRAL heritage

By Aidan Sheedy

Educational leader Heber Pérez and I spent a lot of time together walking down the San Lucas streets with sporadic interruptions from children shouting “Profe! Profe!” from blocks away. It is obvious how much of an impact he has on his community.

Enter San Lucas Tolimán, a village in southern Guatemala at the base of Lake Atitlán where 93% of citizens are Maya. Where local teachers are the catalysts of social change, looking to reconnect the next generation of leaders with pride in its identity.

When Pérez was a child himself, he noticed the leadership qualities he displayed that could make him a great teacher one day. This all started while trying to navigate his place on the football field.

“I was never a good player, but I was able to tell others how to do it well,” Pérez said through an interpreter. “I could tell from the beginning that there was something special for me, that this was gonna be my future— using my voice.”

Pérez mentioned that one of his biggest motivators for the kids is using his own in-school experiences, when he experienced racism and discrimination.

“I started first grade at seven years old and that whole year was a wash,” he said. “It was hard to go to school because of the way the teachers treated me. It was a very, very rigorous system.”

Pérez teaches a group of Quinnipiac University students about the coffee farming process in San Lucas Tolimán. Photo by Jack Spiegel

The curriculum was centered around colonial values, teaching systems that Maya people don’t adopt in their daily lives. Even classes are taught in Spanish when 30% of the country and the majority of San Lucas primarily speak a Maya language.

“The schools have educated us in a colonial way. The system forces (Maya people) to adapt to an environment different from their own identities, an oppressive model,” he said. “It’s a model that aims to make the young people fit in a particular vision that turns them into laborers for those in power.”

Similar to the colonial term “Americanization” in the United States, the term “Hispanización” comes from a way to describe the forced assimilation of Indigenous Latin Americans to Spanish customs. This includes education systems fit to produce societal contributors in ways that benefit the mother country.

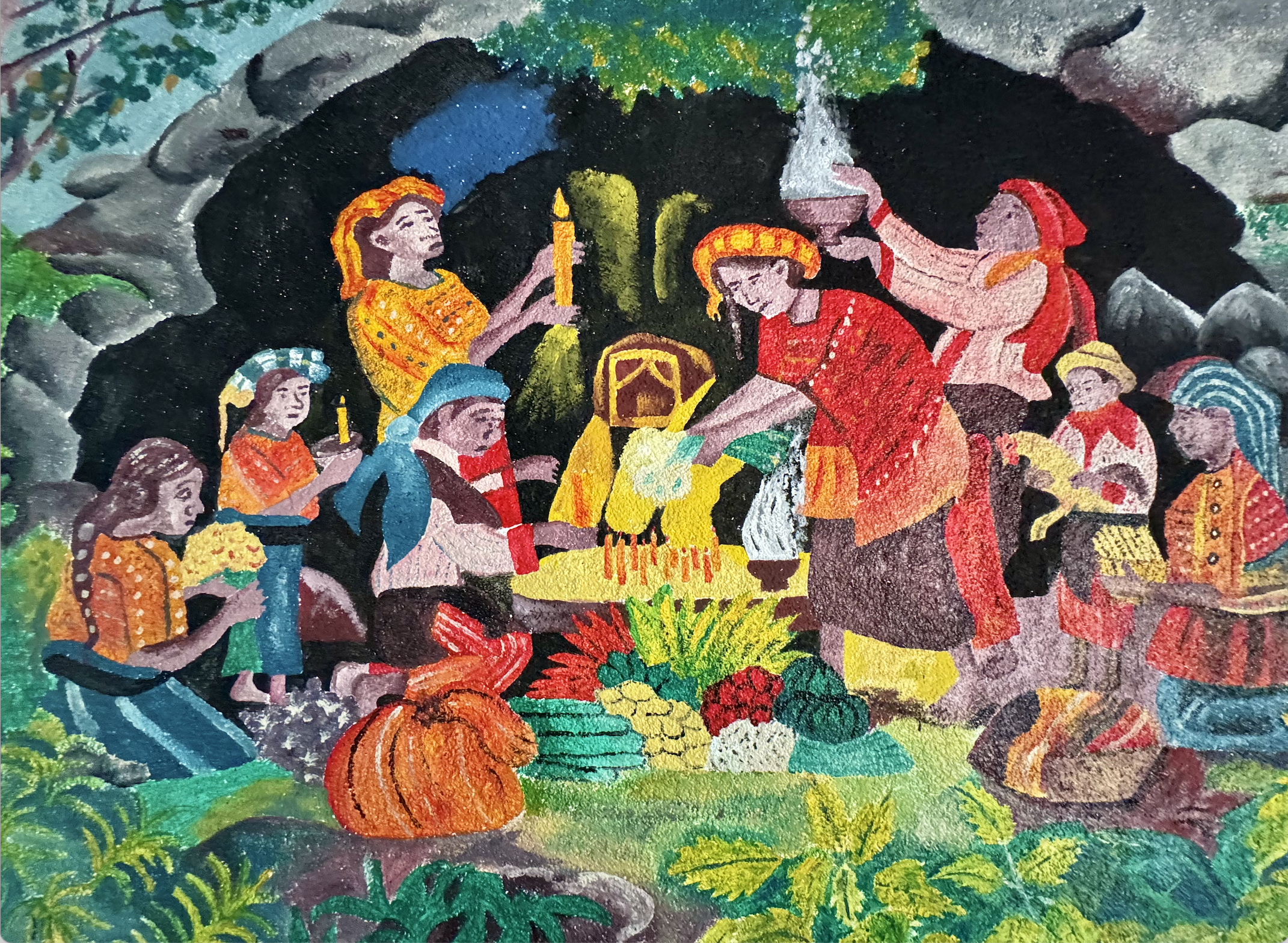

A mural depicting a Maya ritual displayed at a small university in the southern Sololá region. Photo by Aidan Sheedy

“It’s been more than 500 years of invasion,” he said. “(Colonizers) have taken away language, garb, and are taking away our culture, and schools are one of the biggest contributors for this.”

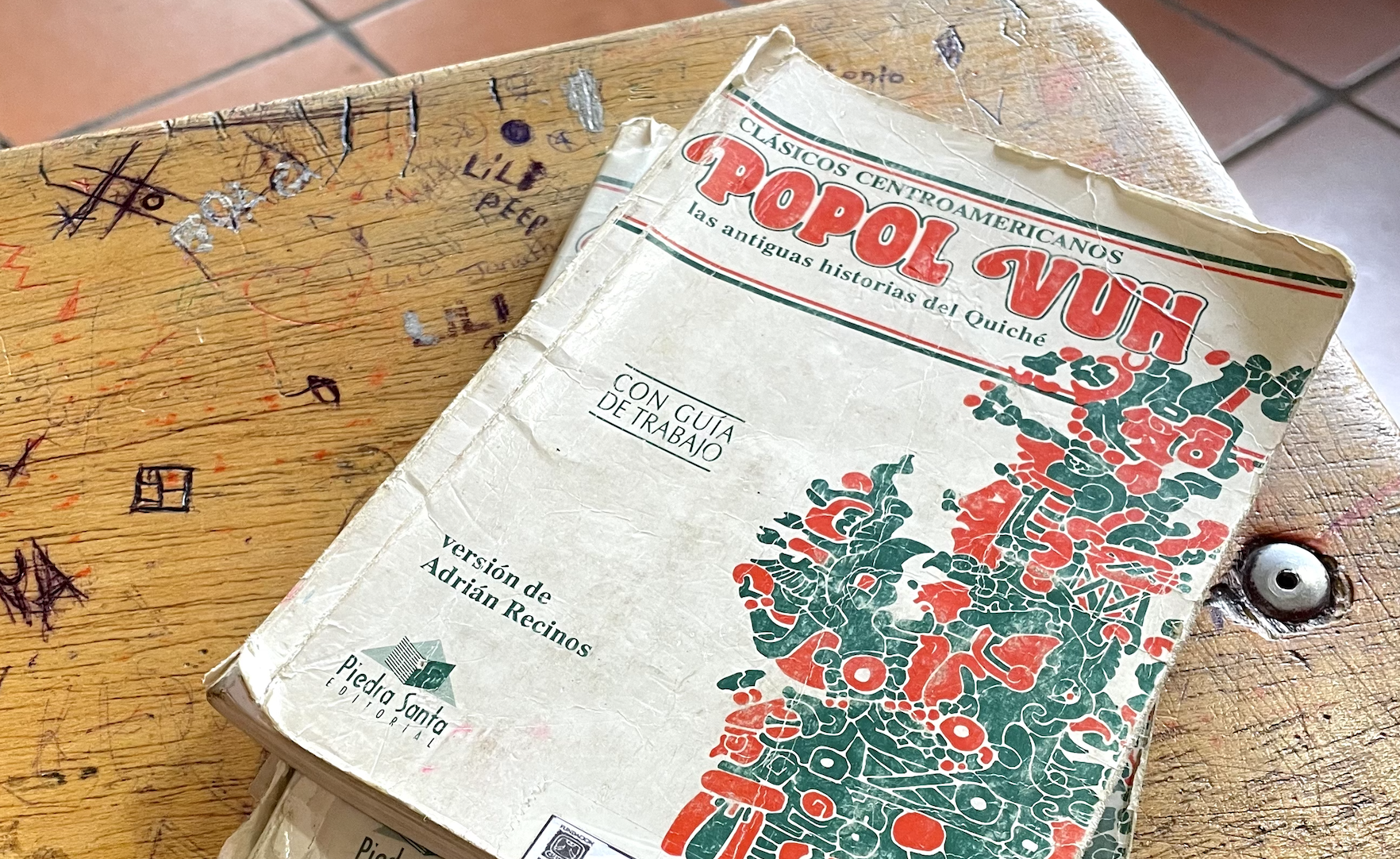

The Maya people are a proud group that became one of the strongest civilizations in Mesoamerica, the Pre-Columbian era. Today, there are over six million descendants to the great kingdom. For over 2000 years, they’ve established their own numeral system, calendar, farming practices, about 30 different languages and even its own text of creation. Unfortunately, Hispanización processes diminish these customs.

“There are these moments where you realize what you’re doing doesn’t allow you to fit in,” he said. “We want to make sure that there is no rejection of identity as Maya educators. Here, a large proportion has lost its identity, they don’t understand the necessary changes to the educational system. That’s why we think differently than the others.”

The education reform in 1996 was a major point in the global peace agreements after a U.S.-backed government carried out a genocide of Mayas. This document included promises like increased Indigenous representation, scholarship grants and Maya emphasis in the civic education programs. Yet, this is not what Pérez has seen.

Today, all of the aforementioned agreements are still listed under “intermediate implementation” by the University of Notre Dame’s Institute for International Peace Studies.

The Popol Vuh, the creationist text of the Mayas and has been translated from the original K’iche’ language over a dozen times. Photo by Aidan Sheedy

The studies are conducted by graduate students at the Keough School of Global Affairs, one of the world's leading centers for studying causes of violent conflict and strategies for sustainable peace.

But while there is little progress done by the government to support Maya people, Pérez preaches to his students to resist the colonial powers and embrace their heritage. This was the case for 23-year-old Fatima Vásquez, who had some great Maya educators in her life.

As a child, my teachers were also indigenous and I think that made me feel safer,” Vásquez said. “When I studied in elementary school, I didn't have problems with that either, most of my teachers were also indigenous and I was always able to wear typical (clothing) without problems.”

A vital component to a child’s education is seeing themselves in their teachers. While Vásquez saw great role models in school, that all changed heading into the workforce.

“When I began to study the career of accounting … it was a very big change because there you could not use the typical costume, only the uniform, and not all the teachers were indigenous,” she said.

Vásquez soon found solidarity in the accounting field, surrounded by other Maya people and said she felt very supported— a countered experience to Pérez. At the same time, Vásquez’s educational experience is confirmed by 17-year-old peer Dulce de la Cruz Ajcalón.

Street view from the downtown of San Juan La Laguna, Solola. Photo by Aidan Sheedy

Ajcalón saw a difference in learning from Maya educators in a private school. But after a shift in her alma mater’s administration, the new students are seeing substantial changes to the philosophies.

“I have friends there who say that the teachers are not the same,” Ajcalón said. “They don't know us. If (students) can't express their issues, then they left behind what things are like in the Maya worldview.”

And that’s Pérez’s fuel for the fire. Even when we see great educational models utilize Maya culture, it shifts after more powerful figures take over and dismantle what came before.

Pérez needs this generation to stray away from being influenced by those in power. Just like Ajcalón said, they need students to cease thinking in a colonial mindset.

“I have respect for all cultures, but what I don’t understand is why (non-indigenous Guatemalans) have been insulting to us,” Pérez said. “They’ve used us. If we have seen and lived these injustices, we cannot continue to think and live like them.”